The post-quantum signature trilemma

When people compare post-quantum signature schemes, a lot of the time, me included, the conversation often collapses into benchmarks. How fast is verification. How big are signatures. How many microseconds here, how many bytes there. That information matters, but it misses something more fundamental.

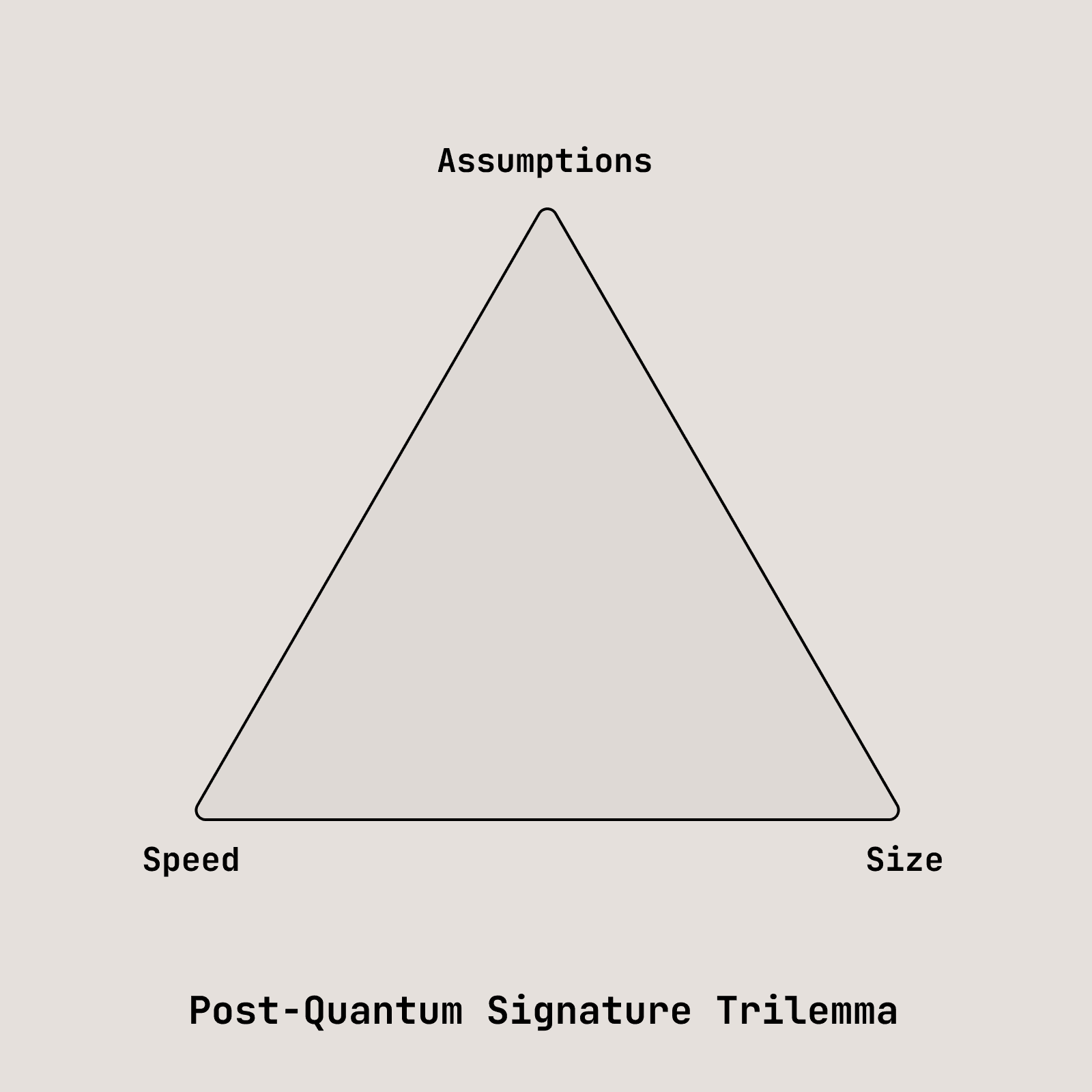

There is a structural trade-off in post-quantum signatures that shows up everywhere once you start looking at them. This isn't necessarily novel but I rarely see it stated explicitly. Every post-quantum signature scheme is making a choice about where to pay its costs, and those costs show up along three dimensions; speed, size, and how conservative the underlying security assumptions are.

You can optimize two of these reasonably well but there is yet to be a reasonable candidate that hits all three.

I call this the Post-Quantum Signature Trilemma

This is not a complaint and certainly not a reason to hold off migration to post-quantum crypto. It is simply what the design space looks like once the algebraic structure behind classical signatures is no longer available.

Classical signatures like ECDSA and EdDSA sit on a very compact structure. That structure gives you small keys, small signatures, and fast operations, but it also gives quantum algorithms something to grab onto. Once that structure is gone, we replace it with one of a small number of options: large linear algebra, massive hashing, or more even exotic constructions.

Each of those choices pushes cost into a different place.

Lattice-based signatures, such as ML-DSA, tend to do reasonably well along the speed dimension, but lean away from the size vertex. They are fast enough that speed rarely becomes the dominant constraint. The cost you pay is primarily in size. Keys and signatures are materially larger than what we are used to, and that overhead is unavoidable. On the security side, the assumptions are well studied but not minimal. They rely on structured lattice problems like Module-LWE and Module-SIS, which have seen extensive analysis but are newer and more parameter-dependent than classical assumptions. As a result, ML-DSA feels like a pragmatic compromise. It does reasonably well on speed, tolerably on size, and acceptably on assumption complexity, but it does not fully optimise any single vertex.

Hash-based signatures, such as SLH-DSA, optimise heavily for clean and well understood security assumptions. Their security reduces almost entirely to the properties of cryptographic hash functions, which makes the underlying assumptions as conservative and well understood as post-quantum signatures get. That clarity comes at a direct cost in the other two dimensions. Signatures are large and verification is slow, and those costs are not incidental. Even within the scheme family, you can see the trilemma at work. Variants that push toward smaller signatures move away from speed, while variants that prioritise speed move further away from size. SLH-DSA does not try to balance the dimensions. It deliberately plants itself at one corner and accepts the consequences.

So far we have only looked at the two standardised post-quantum algorithms, but this process holds for all of the candidate algorithms also. See this great table by Cloudflare.

Once you see this pattern, it becomes useful to think about post-quantum signatures as living inside a triangle. One corner is speed. One corner is size. The third corner is security margin, meaning how conservative and well understood the assumptions are. Schemes do not sit neatly in the middle. They cluster along edges. Moving toward one corner pulls you away from another.

This framing is not meant to rank schemes as good or bad. It is meant to make the costs explicit. In blockchain systems in particular, this matters a lot. Verification time and calldata size are orthogonal constraints. A scheme that is fine in a TLS handshake may be painful in a smart contract. A scheme that looks expensive today may be the right choice for a long-lived vault with a fifty-year threat model.

What I find problematic is not that these trade-offs exist, but that we often pretend they do not. We talk about "efficient" post-quantum signatures as if efficiency were a single axis. It is not. Efficiency for a validator is not efficiency for a rollup. Efficiency for a hardware wallet is not efficiency for a node provider.

Making the triangle explicit forces better questions. Not "what is the best post-quantum signature", but "where do we want to sit on this trade-off, given our threat model and constraints". It also explains why hybrid designs tend to move along edges rather than magically landing in the center. You can combine schemes to balance risks, but, sadly, you do not get a free lunch.

None of this is a new discovery. Cryptographers have understood these constraints for a long time. What is missing is a shared way to talk about them at the system design level. Once you draw the triangle, we can ground the debate in something tangible.

Post-quantum migration is not about guessing when a quantum computer arrives. It is about choosing which costs you are willing to pay today, and which risks you are willing to carry forward. Being explicit about those trade-offs is the difference between engineering and wishful thinking.