The Birthday Paradox

Introduction

In probability theory, given a set of randomly chosen people, the birthday problem asks for the probability that at least two will share the same birthday. The birthday paradox is that, counterintuitively, in a group of only 23 people there is over a 50% chance that there is a shared birthday. This rises to almost 100% with just over 60 people.

It seems odd that only 23 people are needed in order to have a 50% chance of a shared birthday given 23 random birth dates is considerably lower than all of the possible birthdays people can have: 365. However, this is made more intuitive by considering that the comparisons of birthdays are made between every possible pair of individuals. I.e with 23 people, there are pairs of birthdays to consider. This is well over half of the numbers of days in a year (182.5).

Implications on cryptography

A birthday attack is a cryptographic attack that exploits this paradox. Given the paradox, it is possible to find a collision in a hash function in or operations where is the length of the hash in bits - I will prove this shortly and also give a more exact equation. Some research indicates that quantum computers may perform birthday attacks, i.e find collisions, in or operations [1].

A 128-bit hash would take operations to brute force. It’s hard to grasp how massive this number is and its safe to say that brute forcing a 128-bit hash is still out of reach of modern computers. However, finding a hash collision in a 128-bit hash requires operations. A number quickly becoming within the reach of some modern computers.

I talk more about the problems of hash collisions here.

Proof

For simplicity, the following proof will assume that the distribution of birthdays is uniform throughout the year. It will ignore leap years, twins, and seasonal and weekly variations in birth rates. To formalise this, it is assumed that there are 365 possible birthdays, and that each person’s birthday is equally likely to be on any of these days.

The goal is to compute , the probability that at least two people in a group of persons share the same birthday. However, it is simpler to calculate , the probability that no two people in the room have the same birthday. Given and are the only two possibilities and are also mutually exclusive, .

We can now calculate given = 23.

Assume the first person was born on any given date. Given this, the probability that the second person was not born on the same date as the first person can be computed as . The probability that the third person was not born on the same days as either the first or the second person can be computed as .

We can continue this for all 23 people:

Therefore, i.e .

Generalising to number of people

We can generalise this to a group of people as follows:

The above shows that the birthday cannot be the same as any of the - preceding birthdays.

Therefore

We can test this for :

- the same as above.

We can also test this for any value of , e.g :

It's ineresting to see that with only 60 people in a group, it is almost guaranteed that there will be at least two people with the same birthday.

Using the Taylor series we can also approximate this above equation for number of people as:

Generalising to d-bit hashes

Let’s now discuss how this translates to the cryptographic attack mentioned above. To do this, we need to replace birthdays for d-bit hashes by replacing in the above equation with .

We can now solve for so that :

We have now derived the equation known as the birthday bound for d-bit hashes. This equation tells us how many hashes are required () in order for a d-bit hash to have a 50% chance of a collision.

We can now compute this value for different d-bit hashes:

:

:

:

Demonstration of this paradox in Python

Here's a Python program demonstrating the birthday paradox experimentally: here.

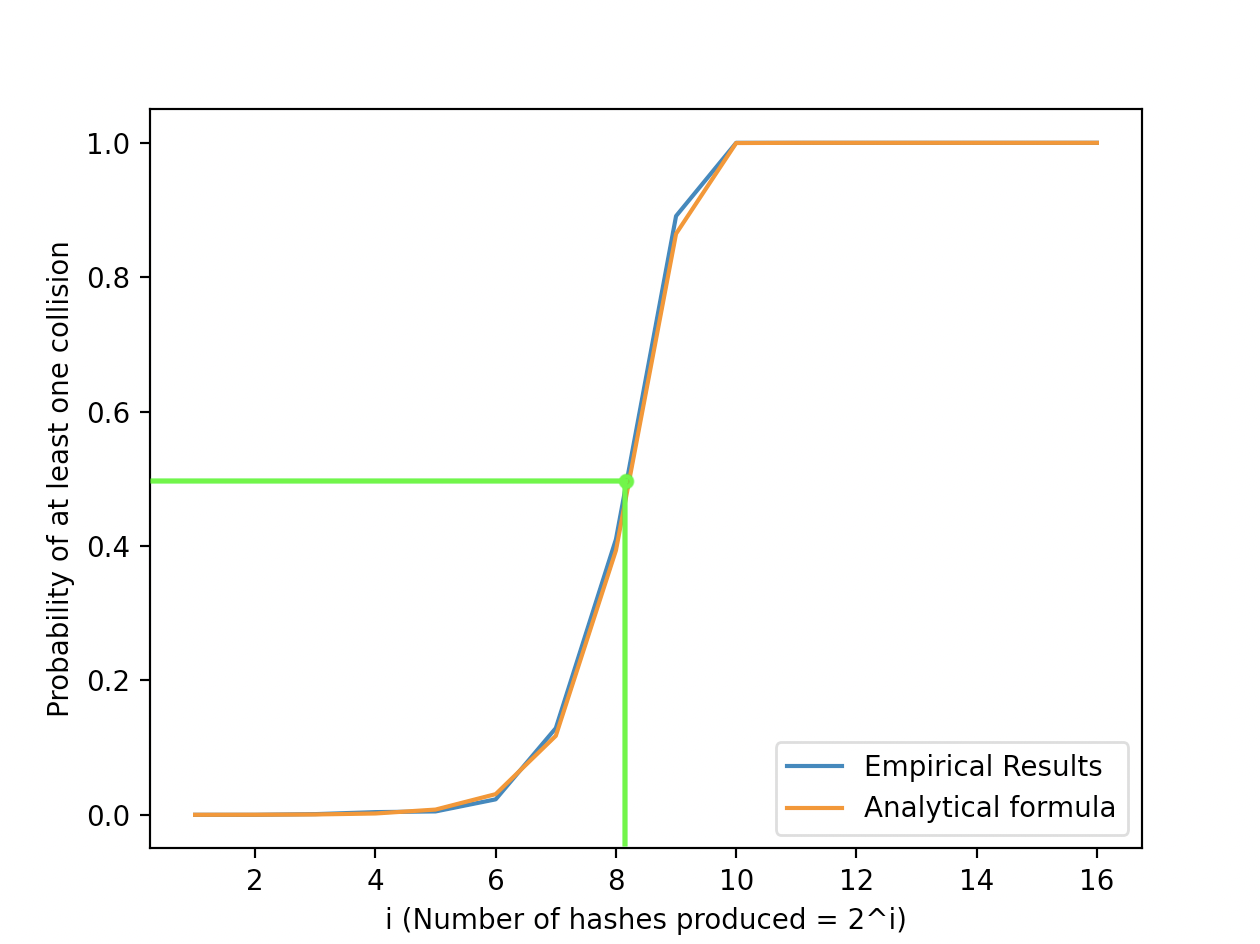

The attached Python program generates 16-bit hashes and checks for at least one collision.

For this, can equal where .

Given that we are dealing with 16-bit hashes, due to the birthday paradox, we would expect a 50% chance of a collision when we generate hashes.

The program runs 1,000 times for each value of in order to check if there is a trend in how many times at least one collision is found. The program then plots the results along side the results calculated from the derived equation, subbing in the relevant value of each time:

Plot of Results

Plot of Results

From the above we can see that the empirical results match almost perfectly with the derived equation. Only 256 hashes are required in order to have a 50% chance of at least once collision in a 16-bit hash, which can take = 65,536 possible values.

References

Note: these references exclude hyperlinks included throughout the document.